Regulatory Framework for Business Transactions - Short Quiz 2

Concept-focused guide for Regulatory Framework for Business Transactions - Short Quiz 2.

~13 min read

🎓 Listen to Professor Narration

Too lazy to read? Let our AI professor teach you this topic in a conversational, engaging style.

Overview

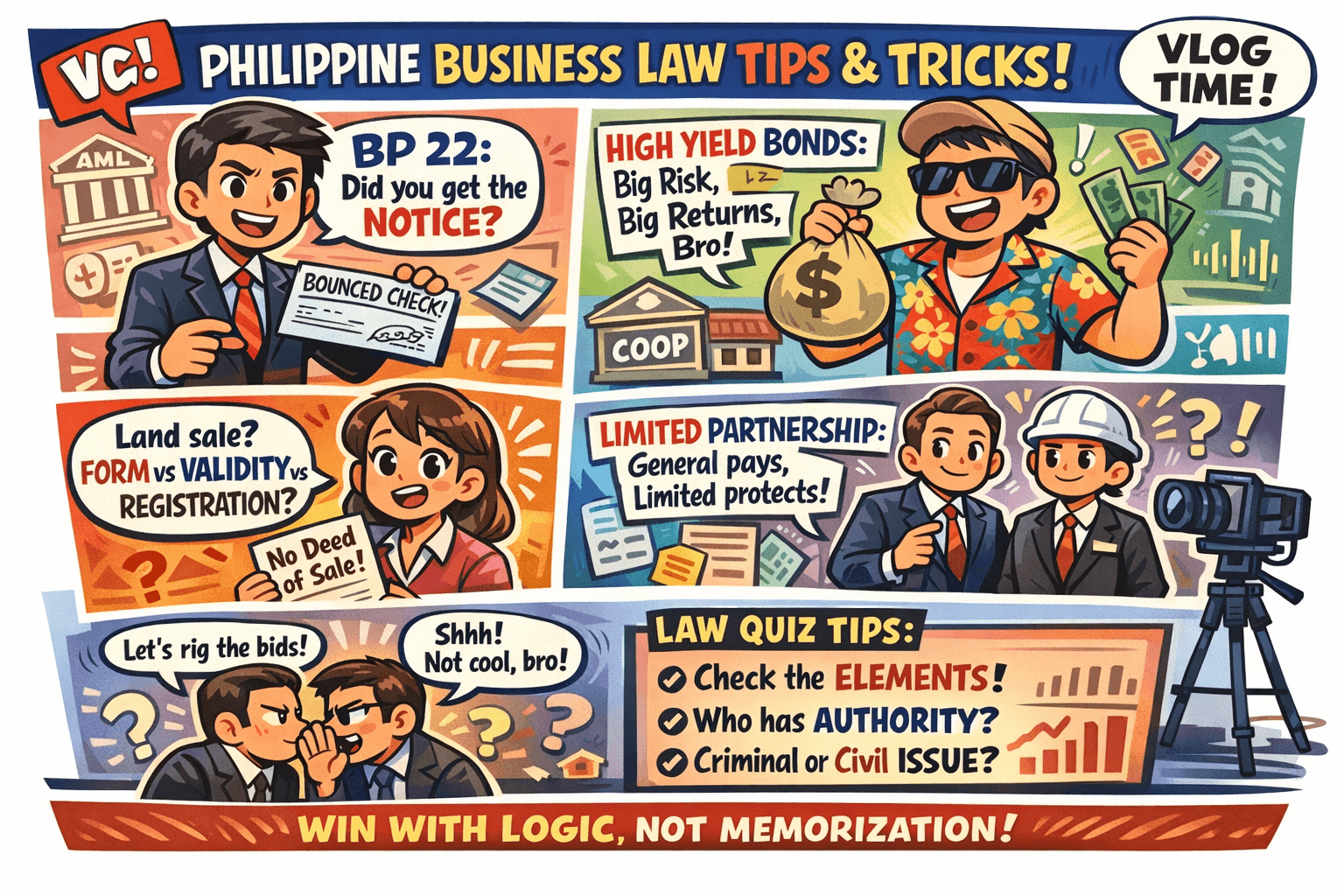

In this vlog-style lesson, we’ll build the mental models you need to answer board-style questions on business transactions and corporate governance—without memorizing isolated rules. You’ll learn how to spot which legal framework applies (sale vs. security device vs. corporate act), how to run the “approval ladder” (board vs. stockholders vs. regulators), and how to reason through liability and remedies when something goes wrong. By the end, you should be able to justify your choices using rule-elements and common exam patterns, not guesswork.

Concept-by-Concept Deep Dive

Stockholders’ Right to Inspect Corporate Records (and Its Limits)

- What it is (2–4 sentences). The right of inspection allows a stockholder to examine certain corporate books and records to protect their interests as an owner. It’s a governance tool: it supports transparency, accountability, and informed decision-making. But it’s not unlimited—corporations can refuse when the request is improper, abusive, or outside what the law considers inspectable records.

What counts as “records” in exam patterns

- Core corporate records. Typical inspectable items include minutes of meetings, stock and transfer books, financial statements, and other official corporate records.

- “Business opportunity / buyer interest” materials. Questions often test whether informal communications, third-party expressions of interest, draft offers, or negotiation materials are part of “corporate records” subject to inspection. The key is whether the item is an official record kept by the corporation in the regular course, and whether disclosure would harm legitimate corporate interests (e.g., confidentiality in negotiations).

- Closely held corporation twist. In closely held setups, inspection disputes are common because minority owners worry about squeeze-outs. Expect “purpose” and “good faith” to be heavily tested.

Step-by-step reasoning recipe

- Confirm standing: Is the requester actually a stockholder (and sometimes: at the relevant time)?

- Identify the item requested: Is it an official book/record or a negotiation/strategy document?

- Check purpose: Is the purpose legitimate (e.g., valuation, monitoring management, investigating mismanagement) or improper (e.g., to aid a competitor, harass, or breach confidentiality)?

- Consider confidentiality and harm: Even with a proper purpose, some materials may be protected or subject to reasonable conditions (time, place, copying limits, NDAs).

- Pick the remedy framing: If denied, questions may pivot to whether the stockholder can compel inspection and under what conditions.

Common misconceptions and how to fix them

- Misconception: “Any document the corporation has must be shown.”

Fix: Inspection typically targets corporate records, not every email, draft, or negotiation memo—especially if disclosure would undermine corporate bargaining. - Misconception: “Closely held means automatic access to everything.”

Fix: Closely held status strengthens the need for transparency but doesn’t erase confidentiality, privilege, or improper-purpose defenses. - Misconception: “Purpose doesn’t matter.”

Fix: Many exam items hinge on whether the stockholder’s purpose is legitimate and in good faith.

Contracts of Sale: Specific Goods, Perfection, and Risk of Loss

- What it is (2–4 sentences). In a sale, ownership and risk don’t always move together in the way students expect. Exam questions often focus on specific goods (identified/particular items), perfection of the sale (meeting essential elements), and what happens if the goods are destroyed before delivery due to a fortuitous event.

Essential elements and “perfection”

- Consent: Clear meeting of minds on the object and price.

- Object: Determinate or determinable; “specific goods” are already identified.

- Price: Certain in money or its equivalent (or determinable under the agreement).

Once these are present, the sale is typically considered perfected—even if delivery hasn’t happened yet.

Risk of loss: the exam logic

- Fortuitous loss before delivery is a classic trap. Students confuse:

- Transfer of ownership (often tied to delivery/tradition in civil-law framing), and

- Allocation of risk (who bears loss when neither party is at fault).

- Many questions ask you to decide whether the buyer still must pay, whether the seller must deliver another item, or whether the obligation is extinguished—based on whether the thing is specific and whether the sale is already perfected.

Step-by-step reasoning recipe

- Classify the goods: specific (determinate) vs. generic (fungible).

- Check whether the sale is perfected: do you have consent + object + price?

- Locate the time of loss: before delivery, after delivery, or during transit.

- Confirm fault: neither party at fault vs. seller’s delay vs. buyer’s delay.

- Apply the risk rule: specific goods + fortuitous loss often triggers a different outcome than generic goods (where the seller can still source replacements).

Common misconceptions and how to fix them

- Misconception: “If the seller still has possession, seller always bears the loss.”

Fix: Possession is not the only determinant; classification of goods and the stage of the contract matter. - Misconception: “Generic and specific goods behave the same.”

Fix: Generic goods usually allow substitution; specific goods do not—so consequences of loss differ sharply. - Misconception: “No delivery means no binding sale.”

Fix: Delivery affects transfer/fulfillment; perfection can occur earlier if essential elements are present.

Pledge and Deficiency: When the Creditor Can Still Collect

- What it is (2–4 sentences). A pledge is a security device where personal property is delivered to secure an obligation. If the pledged thing is sold and the proceeds don’t cover the debt, the exam question becomes: can the creditor still collect the unpaid balance (the deficiency), and under what conditions?

The deficiency rule: what exams usually target

- General approach: Many board-style items test whether deficiency recovery is allowed only if there is an agreement permitting it, or whether it’s barred by default. The key is to read the question for phrases like “unless stipulated,” “in the absence of agreement,” or “expressly agreed.”

- Public sale and proper process: Questions may also test whether the sale was done according to required procedures; improper sale can change remedies.

Step-by-step reasoning recipe

- Identify the security device: pledge (movable with delivery) vs. mortgage (immovable) vs. chattel mortgage (movable with registration).

- Confirm sale occurred: Was the collateral validly sold according to required rules?

- Compare proceeds vs. debt: is there a deficiency?

- Look for stipulation: does the contract allow deficiency recovery or waive it?

- Conclude remedy: deficiency claim allowed/limited/denied depending on the governing rule and stipulation.

Common misconceptions and how to fix them

- Misconception: “Creditor always gets deficiency automatically.”

Fix: Some security arrangements restrict deficiency recovery unless there’s an express stipulation. - Misconception: “Pledge and chattel mortgage have identical deficiency rules.”

Fix: They are related but not identical; exam writers love switching labels to see if you’re tracking the correct statute/doctrine.

Corporate Share Issuance: Authorized vs. Issued, Board vs. Stockholder Approval

- What it is (2–4 sentences). Corporate questions in this set revolve around who has the power to issue shares and when stockholder approval is required. The trick is to separate (1) issuing shares already authorized in the articles from (2) increasing the authorized capital (which changes the articles) and (3) special situations like pre-emptive rights or issuance of a new class.

The share-number vocabulary you must master

- Authorized shares: the maximum shares the corporation is allowed to issue under its charter/articles.

- Issued shares: shares that have been released/sold/allocated by the corporation.

- Outstanding shares: issued shares still held by shareholders (not reacquired as treasury shares).

- Unissued shares: authorized but not yet issued (the “room” you can still issue without amending the charter).

Board action vs.

🔒 Continue Reading with Premium

Unlock the full vlog content, professor narration, and all additional sections with a one-time premium upgrade.

One-time payment • Lifetime access • Support development

CPALE App and tools to supercharge your learning experience

CPALE Journal Entry Generator

Convert plain English transactions into accounting journal entries instantly. Perfect for accounting students and professionals. Simply describe a transaction like 'Bought supplies for $5,000 on account' and get the proper debit and credit entries.

Join us to receive notifications about our new vlogs/quizzes by subscribing here!